-

RESOURCES

National Climate Change Action Plan

Mandate

To address this global crisis (In response to what has essentially become a global crisis), the Philippine government has enacted the Climate Change Act (Republic Act 9729) as amended that provides the National Framework Strategy for Climate Change, policy framework with which to systematically address the growing threats on community life and its impact on the environment. The Climate Change Act establishes an (organizational structure), the Climate Change Commission as lead national government agency to put forward the national climate agenda and operates within the following functions: (and allocates budgetary resources for its important functions these functions include)

- the formulation of a framework strategy and program, in consultation with the global effort to manage climate change,

- the mainstreaming of climate risk reduction into national, sector and local development plans and programs,

- the recommendation of policies and key development investments in climate-sensitive sectors,

- the assessments of vulnerability and facilitation of capacity building

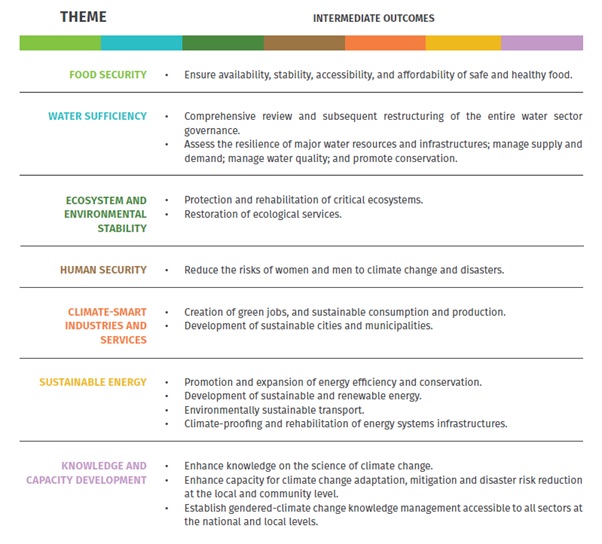

The National Framework Strategy on Climate Change emphasizes the Philippine approach on climate change where climate change adaptation serves as an anchor strategy and climate change mitigation as function of adaptation. Within the Framework, the country developed a National Climate Change Action Plan (NCCAP) that outlines a long-term program and strategies for climate change adaptation with the national development plan for 2011 to 2028 and focused on seven thematic priority areas: food security; water sufficiency; ecosystem and environmental stability; human security; climate-smart industries and services; sustainable energy; and knowledge and capacity development.

NCCAP M&E

Monitoring and evaluation has gained a secure position in the global climate discourse during the last decade, a traction from which further progress could be made. This is relatively due to the increasing public demand for measurement and transparency in the use of public resources for climate action. The NCCAP has raised the public’s belief about the ability of the national and local governments to put in place initiatives that heighten accountability, transparency, and public participation in the implementation of climate change programs.

The Climate Change Commission’s journey in institutionalizing and mainstreaming climate actions into the planning and budgeting process of the government began with small but certain steps. For the first time in 2011, the government has put forth substantial efforts through the NCCAP to communicate the development pathway of the country amidst climate change, and linking the relationship and roles of oversight agencies in achieving the target outcomes for 2012-2028.

-

RESOURCES

NCCAP M&E 2011-2016

INTRODUCTION

The NCCAP serves as a baseline in designing national priority programs that addresses the needs of the most climate-vulnerable sectors. In this context, it directly addresses the country’s commitment to the 2015 Paris Agreement on Climate Change through the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Through the NDCs—long-term goal for adaptation—countries commit to undertake and communicate increasingly ambitious efforts towards achieving the global climate goal.

The NCCAP M&E 2011-2016 Report focuses on the readiness of the national government agencies wherein manifested evidence of key governance factors essential for effective and successful climate adaptation were reviewed. Parameters included were political leadership; stakeholder support; institutional development; use of climate change information; appropriate use of decision-making techniques; and consideration of barriers to adaptation, funding, technology development, and adaptation research.

Finally, the Report introduces approaches for monitoring and evaluating of adaptation to climate change within governance systems. It also discussed the functionality of climate mitigation looking into the mitigation co-benefits relating to the thematic themes of NCCAP. It outlines whether and how each targeted outcome of the NCCAP thematic theme could operate within each other’s dimension or systems of interests, and also highlights the contributions to enhancing adaptive capacity, reducing vulnerability and sustained development.

Taken together, may this document serve to provide a clear, concise baseline of the NCCAP’s achievements and areas of improvement; and perhaps, even inspire better solutions— as we work towards our mission for a nation that is climate resilient and climate-smart.

NCCAP THEME INTERMEDIATE OUTCOMES

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Climate change adaptation defines the planning and development mindset of the government which requires a shift from a business-as-usual perspective to a climate resilient investment, planning and policy decisions. This demonstration of commitment to adapt is more than intensifying awareness at the national government aimed at steering all facets of concerted efforts and initiatives to augment climate sensitivities and accelerate climate resilience across all sectors and levels. The enactment of Republic Act No. 9729 or the Climate Change Act of 2009 provided a policy framework to address sensitivities to climate change through the development of National Framework Strategy (NFSCC), adopted in April 2010. The Framework Strategy emphasizes the Philippine approach on climate change where climate change adaptation serves as an anchor strategy and climate change mitigation as function of adaptation. Within the Framework, the country developed a National Climate Change Action Plan (NCCAP) that outlines a long-term program and strategies for climate change adaptation with the national development plan focused on identified seven (7) thematic priority areas, namely; 1) food security; 2) water sufficiency; 3) ecosystem and environmental stability; 4) human security; 5) climate-smart industries and services; 6) sustainable energy; and 7) knowledge and capacity development. The phases of implementation under NCCAP is aligned with the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Plan (NDRRMP) and the Philippine Development Plan (PDP), the country’s development framework that seeks to address poverty, create employment opportunities and achieve inclusive growth.

The Climate Change Commission in partnership with SupportCCC of GIZ, prepared the NCCAP monitoring and evaluation (M&E) report focusing on the status of mainstreaming climate change in the national government agencies envisioned as key players to achieve the goals of the NCCAP. Specifically, the report focuses on the readiness of national government agencies wherein manifested evidence of key governance factors essential for effective and successful climate adaptation are reviewed. Parameters included are political leadership; stakeholder support; institutional development; use of climate change information; appropriate use of decision-making techniques; and consideration of barriers to adaptation, funding, technology development, and adaptation research.

The Report introduces approaches for monitoring and evaluating of adaptation to climate change within governance systems. This has been developed on the basis of a review of existing literature and analysis on the governance dimensions of tackling climate change, as well as interviews and focus group discussions with key government agencies for each thematic area of the NCCAP. It covers both mainstreaming and adaptation context, and is based on theories of change and commitment to NCCAP reporting period.

Status of government readiness illustrated by means of the strength of the enabling policies and corresponding implementation plans and programs; the structure of institutions and capacity that either enable or restrict adaptation; the extent and quality of capacity development; and the management of knowledge systems in the government in terms of relevance, quality and timeliness.

The Report then puts forward programs already implemented as an entry point for mainstreaming and strengthening the enabling environment at the national level vis-à-vis goals of the NCCAP. Discussion of potential flagship programs are already best practices for each thematic theme to build on for the NCCAP updating including cross sectoral gaps and challenges.

The Report also discussed the functionality of climate mitigation looking into the mitigation co-benefits relating to the thematic themes of NCCAP. The Report not only outlines whether and how each targeted outcome of the NCCAP thematic theme could operate within each other’s dimension or systems of interests, but also highlights the contributions to enhancing adaptive capacity, reducing vulnerability and sustained development.

-

RESOURCES

Food Security

FS Adaptation Context

Even as the share of the agricultural and fisheries (AF) sector to the Philippines’ total economic output has been declining over the years, it remains crucial for attaining the country’s sustainable human development goals for two reasons. First, it still is the second biggest contributor to employment in the country next to the services sector. It provides livelihoods and incomes for about a third of the country’s labor force, which are considered to be the poorest - women and men farmers and fisherfolk. Second, it is also indivisible with the concern for national food security. Neither decreases in poverty incidence nor improvements in food security outcomes are attainable without AF development. Despite a general sentiment of public underinvestment in the AF sector in more recent years, it has still contributed a yearly average of 10% to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from 2011 to 20162.

The pursuit of AF sector development in the country has been made much more complex and difficult by climate change and climate-related disasters. Increasingly, the country has been battered by climate-related disasters in the past years, and there is already recognition that the impacts of extreme climate variability, such as El Niño episodes and frequent tropical cyclones, have been partly the cause of the underwhelming growth of the AF sector also in the past years (Cruz, et al., 2017). The geographic and archipelagic characteristics of the Philippines has made the country one of the most vulnerable countries to the impacts of climate change. It ranked the fourth most affected country to weather events after assessing risk data from 1996 to 2016 (Kreft, 2017).

Climate change, in particular climate variability and increasing temperature, pose the most profound adverse effects and impacts on the three fourths of the country’s production systems and communities dependent on the AF sector (Cruz, et al., 2017). These are comprised of the most vulnerable smallholder production systems of the country’s poorest women and men farmers and fisherfolk. Further, extreme climate events could influence poverty by reducing agricultural productivity and raising the prices of staple foods, ratcheting down the poor deeper into poverty trap (Ahmed, Diffenbaugh & Hertel, 2009). In particular, women farmers are disproportionately susceptible (Peralta, 2008).

In general, agricultural production systems are negatively affected by climate variability and extreme weather events (Peras, Pulhin, Lasco, Cruz & Pulhin, 2008). Among the impacts of climate change in the sector are increased incidence of pests and diseases, low crop productivity/ yield, delays in fruiting and harvesting, declining quality of produce, and increased labour costs and low farm income (Tolentino & Landicho, 2013 cited in Cruz et al., 2017). Further, the changing rainfall regimes and increasing temperature at night time could considerably influence the overall productivity of farming systems including stages of planning and production (Tibig, 2001 as cited in Comiso et al., 2013). Specific to rice, the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) estimated that a 1°C increase in temperature in minimum temperature in dry seasons could result in a 10%t decline or 64 kg/ha in grain yield (Peng et al., 2004). On the other hand, higher concentrations of CO2 can significantly increase the yield of many crops due to enhanced photosynthesis (Adams et al., 1998).

While the effect of climate change to the Philippine AF sector is generally adverse, it will vary locally based on crop, location, and magnitude of drought, flood and CO2 concentration (BAR, 2016). It is thus essential to undertake site-specific or downscaled analysis of the combined effects of these factors. In this period, a climate resilient vulnerability assessment (CRVA) was undertaken by the Department of Agriculture to understand the potential site-specific impacts of climate change to municipalities (Palao, et al., 2017). This is an essential first step in building climate resilient agriculture communities.

The high performing rice producing regions/provinces in the country such as Cagayan Valley, Pangasinan, Isabela, Nueva Ecija, Iloilo, and Camarines Sur are significantly exposed to floods and typhoons. The food baskets in Mindanao, i.e. North Cotabato and Maguindanao, are more prone to droughts and El Niño events. The 2016 El Niño season brought pest infestation (e.g., armyworm and rodents) in Central Luzon, SOCCSKSARGEN, and ARMM regions. Moreover, 181,687 farmers (representing 224,843 ha of farmland) are affected by the 2016 drought. Of this group, 54% are rice farmers, 38% maize farmers, and 8% high-value crop farmers (IFRC, 2016).

On the other hand, the Philippine fisheries sector, is exposed to increasing Sea Surface Temperature (SST) that can affect the physiological processes and the seasonality of biological rhythms, altering food webs, and, eventually, fish production (Lansingan & Tibig, 2017). Increasing or abnormally high SST, even just by mere 0.5°C, can push coral reefs over their temperature thresholds triggering coral bleaching (ADB, 2009; Arceo, Quibilan, Alino & Licuanan et al., 2001; Licuanan & Gomez, 2000). Increased intensities of CO2 in the atmosphere could trigger ocean acidification ultimately reducing abundance of aquatic species. Overexploitation and illegal fishing practices and activities are also key threats to the sector’s sustainable development (NEDA, 2017).

For this reporting period, the National Climate Change Action Plan Results Based Monitoring and Evaluation System’s (NCCAP RBMES) strategic priorities under Food Security include the 18 major river basins (MRBs), provinces with the highest poverty incidence and exposure to multiple hazards, regions that are major rice and corn producing areas and specific areas for self-sufficiency. In this reporting period, the climate risks in the Philippine AF sector are expected to have affected the country’s food security goals including the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), indicated by self-sufficiency ratio in rice and maize, food subsistence incidence (MDG 1.9b), average inflation rates among basic food commodities, prevalence of underweight children under five years of age (MDG 1.8) and proportion of households with per capita intake below 100% dietary energy requirement (MDG 1.9a).

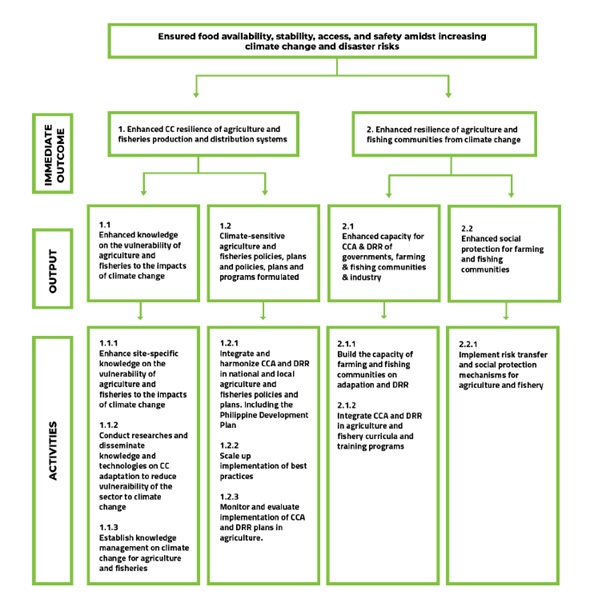

FS Theory of Change

FS Highlights

The less-than-ideal extent of enforcement of the enabling policies and status of institutional environment, mediated by the capacity development and knowledge management support provided, have not yet eliminated all the obstacles to effective and adequate adaptation to fully take place on the ground.

Governance Readiness to Adapt

The complexity of food security and multiplicity of institutions in this thematic area, operating with shared mandate across various levels (from national to subnational) and scale resulted in what appeared to be robust policies, programs and actions. Two sets of actions are seen to have taken place during the period in review. One is crafting new policies, programs and projects while the other was in mainstreaming/integrating climate change and disaster risk reduction management in current policies, plans and programs.

During the reporting period, four policies at the National level guided the formulation of sectoral and sub-sectoral roadmaps, critically selected commodity value and supply chain analysis, among others. These are the following: (i) promoting and/or supporting the further mainstreaming of climate change adaptation, (ii) identifying 10 regions/ provinces and villages in the 18 major river basins as priority for climate adaptation interventions, and (iii) strengthening the critical institutional weaknesses, vulnerability assessment tools for selected crops, livestock and fisheries, cost-benefit analysis for selected crops, livestock and fisheries, identifying mitigation co-benefits in adaptation projects through studies, (iv) establishing criteria and site-specific standards for rural infrastructure are undertaken.

However, coordination problems to cohere and synergize policies, plans and actions across scales and sectors remain, given the current framework of collaboration and the institutions involved in setting policy, oversight, regulation and providing specialized support functions. Many of the significant barriers to adaptation are associated with the absence of an overarching authority capability to mobilize leadership and resources, develop legal and regulatory frameworks for adaptation, and plan for long time horizons required by the uncertainty issues of climate change and its attendant risks. The fragmentation of responsibilities and duplication of functions at the national level are mirrored in the sub-national level in the absence of a rational cooperation arrangement among the attached agencies of the Department of Agriculture (DA) and instrumentalities.

Long before climate change became a target development agenda, the framers of the 1997 Agriculture and Fisheries Modernization Act (AFMA) had the foresight to already take account of climate change, weather disturbances and annual productivity cycles in the formulation of its Agriculture and Fisheries programs. As early as 2011, several recommendations on restructuring the food production governance system using an integrated landscape or ecosystems-based perspective have been conveyed. At the end of this reporting period, the restructuring of the agriculture and fishery sectors remains an unfinished business. This state of partial preparedness serves as the most important underlying factor explaining the state of adaptation implementation and its outcomes.

Accomplishments related to capacity development are more difficult to assess given that the current monitoring systems lacked important details to enable assessment of relevant scope or coverage, i.e., participants targeted (by position, technical expertise, governance level and location), learning objectives, pedagogy and learning approaches employed, and use of acquired knowledge and skills. However, evaluation study of main programs that are reviewed indicate persistent weaknesses in institutional capacity crucial for sustaining the organization and management successes, as well as the lack of required technical competencies by existing personnel. This is exacerbated by the fact that the extension system in the country is decentralized. This means that the Local Government Units are mandated to provide extension services in their localities.

In the area of knowledge management, the sector has taken advantage of the advances in information and communication technology (ICT), especially in the latter part of the reporting period. Several knowledge management (KM) systems supporting agriculture and fishery resources management are established and maintained in the sector. There are also decision support systems available for natural resources valuation, and climate impact modelling that provide science-based options for adaptation action/ decision-making. Vulnerability and risk assessments are still ongoing wherein pre-identified highly critical areas are prioritized.

However, information management in the agriculture and fishery sector is currently distributed among Bureaus and Attached Agencies of the Department of Agriculture. There is no existing integrated KM system to consolidate studies, assessments, technical and project monitoring results, maps, knowledge products, and best practices, to inform coordination. The Agriculture Training Institute, the Apex Extension Organization, and the Bureau of Agricultural Research, and other attached institutions needs to work closely together to ensure the dissemination of technologies to farming and fishing communities, under a decentralized regime in agriculture and fisheries.

Efforts to mainstream climate change and disaster risk reduction at the sub-national level (2012-2016) are through three planning oversight agencies – the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) for the regional and provincial level; the Housing and Land Use Regulatory Board (HLURB) for the Comprehensive Land Use Plan (CLUP); and the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) for the Comprehensive Development Plan (CDP) and Local Climate Change Action Plan (LCCAP).

Adaptation Action Implementation

The DA’s centerpiece program for mainstreaming and integrating climate change in the agriculture and fisheries sector is the Adaptation and Mitigation Initiatives in Agriculture (AMIA). This three-phased package of the DA envisioned to transform the institution and create climate resilient farming and fishing communities. Two other projects of the DA also supported the stocktaking and development of climate resilient agriculture. These are the Philippine Climate Change Adaptation Projects (PhilCCAP) and the Philippine Rural Development Program (PRDP).

The basket of adaptation measures assessed herein include among others, site or location commodity specific vulnerability assessments, and climate resilient practices/ strategies such as integrated farming, water harvesting technologies, sustainable land management, alternative feeds, biogas and composting. For the fisheries subsector, the fish vool was developed, as well as aqua-silviculture activities are implemented. For all the adaptation projects, the mitigation co-benefit was likewise identified.

Other emerging best practices in food security are the establishment of early warning systems to protect lives and livelihoods, productive assets, use of climate information for decision-support in the production, harvest and distribution of agriculture goods and services. Weather-based insurance and credit to support the financial and security requirements of farmers are also availed of during the period in review.

Overall, the adaptation actions taken in this period are relevant and appeared to be robust. However, vis-à-vis targets are inadequate. Still, considering the unfinished business on the preparedness front, principally the incomplete restructuring of the food security governance sector, the limited financial resources and technical capacity of LGUs, and weaknesses in implementation, the adaptation actions taken on the ground are assessed as partially effective because of their being well-targeted and well-designed.

Mitigation Co-benefits

The adaptation projects and best practices for replication of Climate Resilient Agriculture (CRA) has generated mitigation co-benefits, albeit not quantified. Since these CRA are part of the stocktaking and against expert evaluation criteria of climate-smartness of some of these technologies/ practices, descriptions are noted. Some of these are on the enhancement or improvement of soil carbon stocks and soil organic content reduces emissions of methane and other GHG related with rice production and excessive use of pesticides.

Contributions to Enhancing Adaptive Capacity, Reducing Vulnerability and Sustained Development

At the higher outcome level results of the Theory of Change for Food Security during the period in review, it can be said that more food was available in the country. However, its accessibility, especially to the poorest of the poor or marginalized segments of the country’s population was more difficult given that prices are generally increasing. Also, the magnitude of the poor has been increasing owing to population increases. Food utilization and safety both for adults and children have also been decreasing over the period but, remain considerable. Pursuing climate resilient agriculture in view of its sustainability is a way forward for this thematic area to continually ensure food security.

-

RESOURCES

Water Sufficiency

WS Adaptation Context

Water is an irreplaceable building block of societies. It is important for environmental stability. It is the resource base for agriculture development, industrial growth, energy and human security. In the Philippines, agriculture accounts for 82.23 % of water use, followed by the industrial sector at 10.12 %, and industrial use at 7.65 % (FAO AQUASTAT, 2009). Surface water has been the dominant source for irrigating farmlands (FAO, 2011), while domestic and industrial users have relied upon groundwater resources as it is cheaper to store and treat, and its reliability makes it a buffer source of water (NEDA, 2013). The Philippines is blessed with rich water resources coming from 421 major river basins, 79 natural lakes and 4 major groundwater reservoirs (CCC, 2014). The country’s annual renewable water resource is at about 146 billion cubic meters of which 86 % is surface water (NEDA, 2013).

But this abundance is negated by the Philippine Water Resources (WR) sector being highly stressed. The country’s WR sector is ranked 57th most stressed globally by the World Resources Institute (Luo, 2015), for several reasons. First, the stock of surface water was reported to be diminishing at an annual average rate of 13,700 million cubic meters within 1988 to 1993 mainly because of low rate of recharge. Second, the country’s groundwater resources have been depleting because of extensive extraction from industries and households, mainly in urban areas coupled by diminishing groundwater recharge (Philippine Environment Monitor, 2006; CCC, 2014). Third, land use change, increasing population, as well as urbanization and increasing economic activities, have resulted in growing competing demands of various uses (Pulhin et al., 2017). Fourth, surface water in the Philippines, according to the Philippine System for Integrated Economic and Environmental Accounts, have not been fully utilized due to a limited number of reservoirs (CCC, 2014). Fifth, deforestation in the uplands together with pollution and land use change increased siltation and sedimentation deteriorating water quality. Lastly, generally poor and inefficient WR management has been a major contributor to resource waste and untreated wastewater discharges (Manton et al., 2001). Climate change is expected to exacerbate the water shortages from increasing and competing demand and deteriorating water supplies, both in terms of quality and quantity, and this presents significant challenges for water supply and other management concerns, drought preparedness, flood management, and disaster management (CCC, 2014).

There is broad acceptance that climate change-induced variability of rainfall poses the most enormous impact on the Philippine WR sector and the country at large, more than temperature change (Cruz et al., 2017). These variations are observed to be mainly influenced by El Niño and La Niña episodes (Jose & Cruz, 1999; Estoque & Balmori, 2002), monsoons, and mesoscale systems (Cruz et al., 2013); while on the other hand, monthly and seasonal rainfall are affected by the tropical cyclones that enter the country (ibid). Projections using three global climate models (BCM2, CNCM3 and MPEH5) of two downscaled rainfall scenarios (A1B and A2) for the Philippines revealed a generally increasing trend in rainfall for 2020, 2050 and beyond (Cruz et al., 2017). At the same time, these models show a more pronounced rainfall variability wherein peak amount of rainfall increases in wet season, while the dry season is prolonged. Climate-induced variability in rainfall and change in temperature shift the availability of water between too much and too little (Vogel, Smith, & Ray, 2013; CCC, 2014), too much when there is no need and too little when there is a critical need.

Rainfall variability increases the vulnerability of water supply to changes in river flows and the rate of groundwater replenishment (Cruz et al., 2017). Decreased average rainfall during prolonged dry season and increase in evapotranspiration may lower the river flows, reduce available water for irrigation and affect soil porosity and vegetation conditions, ultimately leading to reduced groundwater recharge (Miller, Alexander, & Jovanovic, 2009).

On the other hand, studies project reinforcing relationship between increasing amount of precipitation and warming temperatures which increase evapotranspiration, and which in turn, further increase rainfall (Cruz et al., 2017). Even though total rainfall amount is expected to increase in wet seasons, this may not necessarily result in an improvement in the amount of water recharged, in cases when unusually large amounts of rainfall within a small window of time (Miller et al., 2009). When this happens, the soil is unable to cope with the volume of precipitation occurring within a short period leaving most of the water as surface runoff. Intense rainfall events will also likely promote occurrences of larger flood events. Moreover, Tolentino et al. (2016) modelled several Philippine River basins using climate change projections and while he concluded that a net increase in stream flow is expected in extreme rain events during the wet seasons, this does not necessarily contribute to improvement of water availability for domestic and agricultural use. All these said, water-related infrastructures such as dams, reservoirs and hydropower plants, which are inherently vulnerable to changing temperature and rainfall, will become even more vulnerable (Cruz et al., 2017).

When it comes to disasters, the Philippines is among the countries at most risk from climate-related disasters. It is not only significantly exposed to tropical cyclones but also to floods, landslides and droughts, placing it as one of the most at risk to climate-related disasters across many indices - World Risk Index 2016, Natural Hazards Risk Atlas 2015 and Global Climate Risk Index 2017 (Yusuf & Francisco, 2009; Brooks & Adger, 2003; Eckstein, Kunzel, & Schafer 2017; Verisk Maplecroft, 2015; UNU-EHS, 2016). These extreme events are typically followed by disruptions in the water infrastructure for all water uses – whether for irrigation or industry or domestic use (Cruz et al., 2017). Extreme weather events bring constant threat to those unprepared and unadapted, and the worst-hit are the poorest and most vulnerable.

For this reporting period, the National Climate Change Action Plan - Results Based Monitoring and Evaluation Systems (NCCAP RBMES) strategic priorities under Water Sufficiency include the 18 major river basins (MRBs), nine critical groundwater areas, provinces with the highest poverty incidence and exposure to multiple hazards, and waterless municipalities. The impacts of the climate-induced risks experienced in this period are expected to have affected the country’s progress towards its water sufficiency, water quality and water availability per capita goals, as well as its targets for Millennium Development Goal (MDGs) 7.7a on access to safe water supply, and to some extent, Sustainable Development Goal 6.5.1 on the implementation of integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM).

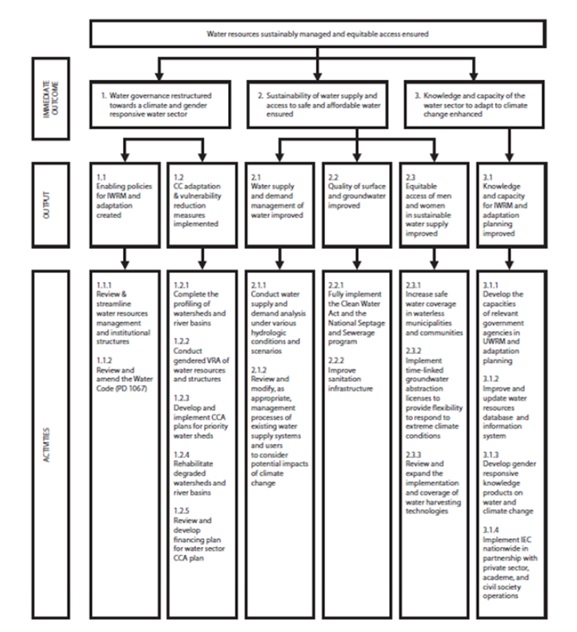

WS Theory of Change

WS Highlights

Governance Readiness to Adapt

The multiplicity of institutions in the water sector, operating with shared mandate across various levels (from national to subnational) and scale (river basin to point-source utility) resulted in what appeared to be robust policies, programs and actions.

During the reporting period, policies (i) promoting and/or supporting the further mainstreaming of climate change adaptation, (ii) identifying 18 MRBs as priority for climate adaptation interventions, and (iii) addressing and/or promoting adaptation actions to specific climate-related risks are enacted. These guided the formulation of sectoral roadmaps with set priority development objectives to be achieved in the long term, as well as adaptation-contributory programs to achieve the development targets set in the roadmaps.

However, coordination problems to cohere and synergize policies, plans and actions across scales and sectors remain given the current framework of collaboration and the institutions involved in setting policy, oversight, regulation and providing specialized support functions. Many of the significant barriers to adaptation are associated with the absence of an overarching authority capability to mobilize leadership and resources, develop legal and regulatory frameworks for adaptation, and plan for long time horizons required by the uncertainty issues of climate change and its attendant risks. Sadly, the fragmentation of responsibilities and duplication of functions at the national level are mirrored in the river basin infrastructure.

It is not that the sector is not self-aware. As early as 2013, several recommendations on restructuring the water governance landscape have been conveyed. These to this date however, still await enactment. At the end of this reporting period, the restructuring of the water governance sector remains an unfinished business, but highly relevant, and urgently needed. This state of partial preparedness is defined as the most important underlying factor explaining the state of adaptation implementation and its outcomes.

Accomplishments related to capacity development are more difficult to assess given that current monitoring systems lacked important details to enable assessment of relevant scope or coverage, i.e., participants targeted (by position, technical expertise, governance level and location), learning objectives, pedagogy and learning approaches employed, and use of acquired knowledge and skills. However, evaluation study of main programs that are reviewed indicate persistent weaknesses in institutional capacity crucial for sustaining the organization and management successes as well as the lack of required technical competencies by existing personnel and weak human resource capabilities.

In the area of knowledge management, the sector has taken advantage of the advances in information and communication technology especially in the latter part of the reporting period. Several knowledge management systems supporting water resources management are established and maintained in the sector. There are also decision support systems available for natural resources valuation, and climate impact modelling that provide science-based options for adaptation action/decision-making. Vulnerability and risk assessments are still mainly ongoing wherein pre-identified highly critical areas are prioritized. While the National Water Resources Board (NWRB) coordinates the information management in the water resources sector, there is no existing integrated knowledge management system to consolidate studies, assessments, and technical and project monitoring results, maps, knowledge products, best practices, etc. to inform coordination.

Adaptation Action Implementation

The basket of adaptation measures assessed herein include water climate-proofing of water infrastructure, disaster risk reduction/early warning systems, water supply and demand management, water quality management areas, enforcement of climate-resilient designs, cash-for-work for climate change adaptation and mitigation. Some represent responses to the specific climate-related risks of the sector and the river basins (rainfall variability, drought), some to general environmental problems (water pollution), and others to disaster risk. All address both specific climate change and general sustainable development goals.

Overall, the adaptation actions taken in this period are relevant and appeared to be robust. However, vis-à-vis targets are inadequate. Still, considering the unfinished business on the preparedness front, principally the incomplete restructuring of the water governance sector, the limited progress in integrated river basin management and development master plans preparation, and weaknesses in implementation, the adaptation actions taken on the ground are assessed as Partially Effective because of their being well-targeted and well-designed.

Mitigation Co-benefits

Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) constitutes planning for water extraction for various uses. Within this context, the estimated cumulative mitigation potential from efficient use of irrigation water by Alternative Wetting and Drying (AWD) in rice production is the most promising co-benefit of the IWRM adaptation measures in the water sector. Furthermore, programs related to wastewater management (e.g. domestic wastewater treatment) related to the implementation of the Clean Water Act can have significant mitigation co-benefits.

However, no report on the mitigation co-benefits of adaptation measures related to the NCCAP water sufficiency theme can be made for the reporting period. Analysis of mitigation options are still ongoing and target to be finalized by the end of 2019.

Contributions to Enhancing Adaptive Capacity, Reducing Vulnerability and Sustained Development

The contributions of adaptive actions undertaken in this period to cumulative progress towards water sufficiency as one of the goals of sustainable human development are assessed along four outcome indicators, namely: Water Availability Per Capita (WAPC); Water Withdrawal to Availability (WWA); Water Supply Coverage (WSC); and Water Quality of Priority River Systems. The first two are water supply/availability indicators, the next is a water demand/access indicator, and the last a water quality indicator mediating both availability and access.

While water governance efforts generally succeeded in bringing more water to the people in this period, with water supply coverage de facto increased from 84.8 % in 2010 to 86.6 % in 2016, there is cause for concern because in the same period, water availability decreased. The low WAPC and WWA are indications that the country is water-stressed.

For water quality, which affects the availability and access depending on use, majority of the priority river systems are unfit sources of drinking water (Class A, with treatment). These outcomes reiterate the need to complete the water sector governance restructuring, to enhance the capability of policy-making, oversight, regulatory and management substructures at various levels and scales for climate-adaptive integrated water resources management.

-

RESOURCES

Ecological and Environmental Stability

EES Adaptation Context

The Philippines is considered one of only 17 megadiverse countries in the world. Unfortunately, it is also one of the hottest of hotspots making it among the top ten in the world with the greatest number of species threatened with extinction (CI, 2013; CEPF, 2001). The primary threats to stable and healthy functioning of ecosystems in the Philippines are largely anthropogenic in nature (Cruz et al., 2017). The decline or loss of highly diverse ecosystems will limit ecological processes that enhance diversity, increase their resilience and ability to survive over time. The health of ecosystems ensures the integrity of ecological processes that sustain the provision of Ecosystem Goods and Services (EGS), for instance in the case of watersheds - water, food, fisheries, regulation of water flow, minimization of siltation in waterways, and recreation. And often, it is the asset-less poor dependent on natural resources for their livelihoods and on common property resources for their basic needs that are most affected by ecosystems decline.

Resource use behaviors in the country characterized by exploitative extraction of natural resources, drastic conversions of land into agricultural and built-up areas, and myopic considerations of externalities and natural interactions (such as the introduction of exotic species) have resulted in the following (Cruz et al., 2017): (1) reduction of forest cover from 70 to 20 percent just within a century from 1900 to 1999; (2) decline in mangrove forests area by more than half of its extent in the early 1920s (Pulhin, Gevana, & Pulhin, 2017); (3) over-exploitation of coastal and marine ecosystems; and (4) ultimately, as a natural consequence, reduction of natural capital and biodiversity, and the impairment of ecosystems’ ability to deliver environmental goods and life-sustaining services (Cruz et al., 2017). Further, lack of consideration of upstream-downstream interactions within an integrated ecosystems perspective had negative cross-scale effects particularly on downstream ecosystems where, for example, despite having no direct human intervention, coastal zones and beach topography have been observed to have significantly changed (Cruz et al., 2017).

And with the changing climate, the sustainability of staying on a path of business as usual, even with continuing best practices but predicated upon past/stable climate conditions, where terrestrial and biodiversity in the country are already in degraded conditions and coastal systems naturally exposed, is untenable (Watson et al., 2012).

The known climate change (CC) impacts in the Philippines include: firstly, strong winds and tropical cycles which are the primary determinants of the future architecture (i.e. forest structure, composition and function) of the country’s forests (Cruz et al., 2017). Forest ecosystems and biodiversity are vulnerable to high temperatures and extended dry periods. Lasco et al. (2005) revealed that in Central Luzon, local perception points to a positive relationship between extended dry periods during El Niño episodes and the alteration of grasslands, agroecosystems, and forests caused by frequent fire occurrences. Warming temperatures and changing rainfall regimes where the arrival of the rainy season gets delayed affect the flowering and fruiting cycles/gestation timelines of certain trees and some plants and wildlife are displaced in their preferred habitats due to increasing temperature (Cruz et al., 2017).

Secondly, marine and coastal ecosystems including mangroves have considerable degree of natural exposure to sea level rise, changes in temperature, rainfall, tropical cyclones, and storms (Cruz et al., 2017). These stimuli are sources of major climate-related hazards such as beach erosion, flooding, deterioration of coastal ecosystems, and salinization either caused or worsened by sea level rise and tropical cyclones (ibid). Moreover, increasing or abnormally high ocean temperature, even just by a mere 0.5 degree Celsius, can push coral reefs over their temperature thresholds triggering coral bleaching (ADB, 2009; Arceo, Quibilan, Alino & Licuanan et al., 2001; Licuanan & Gomez, 2000). Then there is ocean acidification caused by increased absorption of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere which could generally decrease the ability of many marine organisms to build their shells and skeletal structure, slow down the overall growth of marine organisms, slow down reproduction, and thus reduce their abundance (Cruz et al., 2017). Freshwater ecosystems, such as lakes and rivers, on the other hand, are particularly vulnerable to excessive rainfall events which could result in heavy siltation from debris flows, mudflow, soil erosion and landslide incidents (ibid).

The confluence of natural exposure, unsustainable practices and over reliance on EGS by the poorest and most vulnerable communities, when conjoined by governance and management issues that stem from upstream-downstream or cross-scale dynamics make environment and natural resources management (ENRM) a tall challenge. This made imperative the adoption of holistic and integrated ENRM frameworks. In the past two decades, several such approaches have been adopted, applied and further evolved in the Philippines including sustainable integrated area development (SIAD), integrated watershed management (IWM), integrated coastal management (ICM), integrated ecosystem management (IEM) and today with the complication brought on by climate change, ecosystems-based adaptation (EbA).

For this reporting period, the strategic implementation priorities under the Ecological and Environmental Stability (EES) set by the National Climate Change Action Plan (NCCAP) include EbA responses to specific climate-induced risks in the Protected Areas (PAs) and Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs) nationwide, the country’s 19 Priority River Systems and 18 Major River Basins, and in ten pilot Ecotowns. Several outcome areas under this theme are shared targets with the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) including: improvements in forest cover (MDG 7.1); sustainable management of critical coastal and marine habitats (MDG 7.5); and change in conservation status of threatened and/ or protected species (7.6).

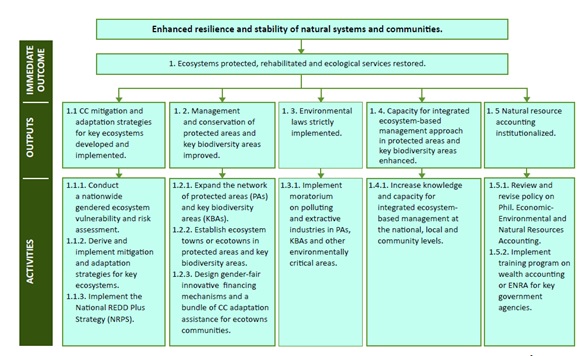

EES Theory of Change

EES Highlights

Policies are in place to enable the mainstreaming of climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction and, more recently, capture climate change mitigation co-benefits from adaptation actions. Adaptation actions implemented in the Energy and Natural Resources (ENR) sector showed that, while some are considered distinctly Ecosystem-Based Adaptation (EbA) and actions intended to manage and address the anthropogenic sources of environmental degradation are recognized as contributing to Ecosystems and Ecological Stability (EES) and ecosystem resilience in the face of climate change, these are not robust enough in anticipating and preparing for the irreversible impacts of climate change.

Governance Readiness to Adapt

Policies on the integrated management of watersheds, forests and protected areas and corresponding initiatives to mainstream climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction (CCA-DRR) in efforts to address anthropogenic drivers of ecosystems degradation have been enacted prior to the NCCAP. The required plans and operationalizing programs of these policies are continuing up to the present time anchored in river basin master plans with EbA as a key strategy to be used in setting objectives and means for achieving ecosystem resilience and ecological integrity in the formulation of the country’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC). Numerous projects and programs provided advisory and capacity development support, mainly to the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) and the Ecotown Framework Demonstration of the Climate Change Commission (CCC), which contributed to CCA-DRR mainstreaming at the national and local levels.

However, environment and natural resources governance continues to be affected with problems of overlapping, sometimes conflicting, institutional mandates on one hand, and fragmentation of, and disconnects in, management actions on the other. Conflicting boundary claims on the ground based on various tenurial instruments continued in the reporting period which has resulted in responsibility, authority and accountability not being clearly defined as bases for coherent and convergent action and services delivery. Capacity development interventions to help address the institutional capacity gaps and to provide the assistance necessary to integrate climate change considerations into these existing management regimes to graduate them into EbA are thematically relevant to continuing efforts to manage and arrest ecosystems degradation. Inadequate information prevents assessment of adequacy, efficient use of resources and effectiveness. While capacity development activities continue to be implemented, the weaknesses of the ENR institutional environment have persisted. It is too early in the adoption curve of the EbA to value the capacity development initiatives undertaken in this period to assess effectiveness in facilitating EbA mainstreaming.

Furthermore, knowledge management system that facilitates timely and informed decision-making regarding preparedness actions for EbA remains fragmented in ENR sectors. It is unclear how all the aforementioned knowledge management systems exchange and share information to facilitate decision-making for ENR and EbA. Neither the DENR nor the CCC has established a central management information system as provided in the Climate Change Act of 2009.

Adaptation Action Implementation

Overall, all the actions undertaken in this period are relevant both to ENR management and EbA. Most are effective in reducing the anthropogenic pressures to the declining ecosystems. But as of yet, inconclusive as to their effectiveness in terms of enhancing the ecosystems’ climate resilience, immaturity of the EbA interventions, and the remaining issues and problems besetting both ENR governance and EbA, it is concluded that the aggregate efforts are still inadequate to realize either sustainable management of ecosystems or climate resilient ecosystems. Information on only two financing mechanisms for ENR and EbA programs was made available in the reporting period (i.e., Integrated Protected Area Fund, and People’s Survival Fund) which makes the assessment of available financing as an attribute of preparedness impracticable for the reporting period.

Mitigation Co-benefits

While no report on the mitigation co-benefits of adaptation measures related to the EES theme can be made for the reporting period, there are individual projects that already reports contributions to CO2 reductions, sequestered CO2 and removal of CO2 emissions from project sites in the forestry sector. It should be noted that the analysis of the country’s mitigation options is still ongoing and target to be finalized by the end of 2019.

Contributions to Enhancing Adaptive Capacity, Reducing Vulnerability and Sustained Development

Cumulative progress along forest cover, water quality of priority river systems, trends in the concentration of threatened species, and damages from climate-related disasters, have been effective but only to a limited extent. This makes imperative the strengthening of the implementation of integrated ecosystems management and the transition towards EbA towards a climate resilient environment and natural resources sector.

-

RESOURCES

Human Security

HS Adaptation Context

The Philippines is an archipelago along the Pacific Ring of Fire and surrounded by vast bodies of water. The country is formed by 7,107 islands with an aggregate area of 299,303 sq. km, making up the world’s longest coastline of around 36,000 km (World Bank, 2011). With 75% of tropical cyclones originating from the belt in the North Pacific Basin, the coastlines of the Philippines are rendered highly exposed, making communities residing within naturally susceptible to their risks (DILG, 2014). An average of 20 tropical cyclones enters the Philippine area of responsibility every year (PAGASA as cited in UN OCHA, 2017). At least 60% of the land area of the Philippines and 75% of its population are exposed to multiple hazards, which, aside from tropical cyclones, including floods, droughts and landslides (World Bank, 2011). It is estimated that US$7.893 million or around PhP417 million35 annually on average is lost by the country due to these multi-hazards. This figure constitutes about 69 percent of the country’s social expenditure annually (Alcayna et al., 2016).

Climate change impacts specific to the country, such as increasing temperatures, climate variability of rainfall, increasing intensity and frequency of extreme tropical cyclones, and sea level rise, have altered the daily lives and routines of Filipinos (Villarin, et al., 2016; USAID 2017). Climate projections modelled by the Philippine Atmospheric Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) in 2011 revealed that a mid-range scenario a 0.9° C to 1.1°C increase in temperature in 2020, and a 1.8°C to 2.2°C increase by 2050. In terms of seasonality, mean temperature during summer (March to May) is likely to increase. In general, it is expected that dry days will be more common across the country, (PAGASA, 2011; Rahmat et al., 2014).

The wet season (June to August) is projected to experience increased rainfall on average of 0.9 to 63 percent for Luzon and 2 to 22% for Visayas (PAGASA, 2011). Therefore, days with heavy rainfall (more than 300mm of precipitation) is anticipated to be more frequent in Luzon and Visayas (PAGASA, 2011; Rahmat et al., 2014). Increasing frequency of tropical cyclone events of a devastating scale such as the Super Tropical Cyclone Haiyan is expected to bring the country into a ‘new normal’ (Alcayna et al., 2016; Villarin, et al., 2016).

These shifts in climate worsen disaster risks in various ways. Drought, extreme weather events and climate-induced rainfall variability impact about three-fourths of the country’s crop and livestock production, further worsens the economic situation and food insecurity especially of the poor (Cruz et al., 2017; NEDA, 2015). Too much water during the rainy season and too little during dry season shape streamflow and groundwater recharge, affecting the conditions of watersheds and river basins, dam operation and hydro power generation, the abundance of water supply and its allocation, and water quality (Cruz et al., 2017; Tolentino et al. 2016; Lasco, 2012; Miller, Alexander, & Jovanovic, 2009).

The long dry periods especially during El Niño episodes render grasslands, agroecosystems, and forests prone to the occurrence of fire (Lasco et al., 2005). Tropical cyclone events, rising sea levels, increasing sea surface temperature and ocean acidification put marine and coastal ecosystems at risk to beach erosion, coral bleaching, and salinization (Cruz et al., 2017; USAID, 2017). Meanwhile, excessive rainfall events make freshwater ecosystems vulnerable to heavy siltation from debris flows, mudflow, soil erosion and landslide incidents (Cruz et al., 2017).

In built up areas, high temperature, extreme rainfall and strong winds pose potential damages to urban infrastructures; in coastal settlements, sea level rise and storm surge would not only damage infrastructures but also force the displacement and migration of affected population groups (USAID, 2017).

Climate change is expected to worsen social welfare conditions, especially of the poorest and most vulnerable (children, women, elderly, persons with disabilities). On the health front, it is linked to rising incidences of insect-and rodent-borne, waterborne, food-borne and respiratory diseases as well as heart-related and other diseases/ illnesses (Cruz et al., 2017). In the education sector, it is linked to damaged school infrastructure leading to class disruptions (UNICEF, 2012). The increased occurrences of climate-induced disasters unmatched by public budgetary allocations for their management, has multiplied the vulnerability of the poorest households and communities whose daily struggle is to access and secure basic needs and services.

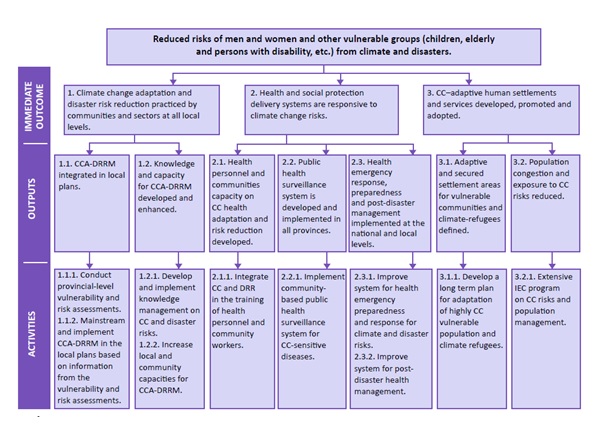

HS Theory of Change

HS Highlights

The Human Security theme of the NCCAP puts emphasis on the need for coordinated climate change adaptation and disaster risk management given their complementary nature and the exacerbating effects of climate change on disasters. While there are a number of initiatives by government agencies to integrate climate and disaster management, these measures, in varying stages, remain fragmented or contained within their sectors. The potential to address common issues across human security that can contribute to overall social welfare remain unrealized. In this monitoring period, much has been done in terms of enabling policy framework, institutions’ readiness, stakeholders’ capacity-building and knowledge management. However, the Philippines still remains as one of the most at risk to climate-related disasters across many indices. Lessons learned from the disaster management community and the experience with Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) in 2013 and beyond reflect that more can be done to enhance the overall adaptive capacity of the country.

Governance Readiness to Adapt

In this period, the accomplishments relative to policy-making, planning and programming towards Human Security consists of two sets of actions: (1) initiatives to converge and legitimize the CCA and DRR agenda; and (2) policies to mainstream CCA-DRR into sectoral (health, education, housing, social protection) institutional structures, plans, and programs. The accomplishments are reflected in four fronts—enabling policies and their implementing plans and programs, institutional capacity, capacity development, and knowledge management.

The initiative for convergence began even before this M&E reporting period. Two main legislations paved the way for CCA-DRR collaboration—the Climate Change Act of 2009 and the National Disaster Risk Reduction Management Act in 2010. Both Acts strongly articulated the relationship of CCA and DRR and mainstreaming climate-induced risks in preparedness and resilience building. Guidelines to mainstream climate change are developed in different sectors, such as health, education and resettlements, and in subnational planning at the regional down to city/municipal-levels (CLUP, CDP). A joint work-plan to implement and synergize the NCCAP and NDRRMP was part of the National Disaster Risk Reduction Management Council (NDRRMC) Circular 02-2010. Relevant capacity development and knowledge management support for involved public health (DOH), education (DepED) and housing institutions and personnel (HUDCC, HLURB), and climate and disaster risk information (DOST-PAGASA) at the relevant scales and levels. In 2014, the Department of Budget and Management (DBM), CCC, and DILG entered into a Joint Memorandum Circular on Climate Change Expenditure Tagging in the Budget preparation.

Local government units play a key role as frontline agencies in addressing climate change and disasters. In recognition of this, the CCC and the NDRRMC entered into a Memorandum of Agreement in 2011 to strengthen the support provided to LGUs in building their capacities to make informed decisions and implement plans and policies to address climate change. In 2014, the DILG issued guidelines on the formulation of the Local Climate Change Action Plans (LCCAP). Funding was also made available to implement adaptation measures through the use of local DRRM fund and the creation of People’s Survival Fund (PSF) in 2011. In the reporting period, the Human Security theme prioritized the most vulnerable LGUs including those within the 18 Major River Basins in the country. Limited information was available to assess the progress of interventions in these priority areas. A report conducted by the Commission on Audit (COA) in 2014 showed that LGUs are challenged with limited staff and capacities to institutionalize and implement a comprehensive risk management in their communities, including compliance to financial reporting and spending of the Local Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (LDRRF).

Adaptation Action Implementation

Mainstreaming efforts through the development of guidelines and framework at various sectors and levels, provision of finance, and capacity building are among the measures highlighted in the reporting period. Advancing early warning systems, risk modelling (such as Project NOAH—Nationwide Operational Assessment of Hazard), and health surveillance platforms (PIDSR, ESR, and SPEED), are among the note-worthy preparatory measures implemented that builds on existing DRR tools.

While these tools are developed, the challenge is for these systems and products to reach even wider coverage, and to be localized, up scaled and out scaled to the extent necessary and possible in the incoming period, keeping in mind the issues on institutionalization and capacities that are yet to be fully addressed.

There are also several DRR measures with adequate focus on socio-economic and political dimensions of managing climate risks that are implemented in this reporting period. These measures (for example, Risk Resiliency Program thru Cash-for Work Projects and Activities from CCAM, Emergency Employment, Housing Program for Informal Settler Families etc.) often come post-disaster ensuring that communities affected stay productive and have access to the most basic needs. The Department of Finance (DOF) also adopted that Disaster Risk and Financing Insurance (DRFI) strategy that made insurance and other financing solutions mandatory for all NGAs, provinces, cities and 1st-3rd class municipalities. Linking relief with development under a building back better framework towards a more adaptive community, remains a big challenge. Lessons learned from the experience during the Typhoon Yolanda showed areas of improvement in terms of management and coordination among agencies and efficient use of resources.

Mitigation Co-benefits

No specific report on the mitigation co-benefits of adaptation measures related to the NCCAP human security theme can be made for the reporting period. Analysis of mitigation options are still on-going and target to be finalized by the end of 2019. However, the Philippine Green Building Code, a referral code to the National Building Code of the Philippines, sets minimum standards aimed at reducing Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions and introducing energy efficiency and sustainable resource use and management. The implementation of this Code can promise to reduce GHG emissions and energy and water consumption by at least 20 %.

Contributions to Enhancing Adaptive Capacity, Reducing Vulnerability and Sustained Development

The outputs of implemented education-, housing- and livelihood- related CCA-DRR are fragmented and do not aggregate into an overall picture of outcomes, i.e., of whether or not vulnerable individuals and communities are better-off after disasters and in general. The available data sets indicate, to some extent, the effects of post-disaster disease management, and to a larger extent, provide a picture of reductions in personal and community insecurity of disaster-affected populations in terms of losses in lives, property, assets and agricultural livelihoods and production:

For the climate-sensitive diseases, the trend for number of lives lost due to cholera, malaria and typhoid are decreasing but unfavorable for dengue.

In terms of the number of people affected (injured, missing, died) due to typhoons, the trend is generally decreasing at the individual and family-levels.

While the trend in damages to agriculture is decreasing, the amount remains to be in the millions. Damages due to drought (2010 and 2015) remained consistently high. No discernable trend as to the damages to infrastructure from landslides and flash floods.

-

RESOURCES

Climate-Friendly Industries and Services

CSIS Adaptation Context

The structure of the Philippine gross domestic product (GDP) by economic sectors from 1998 to 2016 reveals that services is the top growth contributor with more than 50 percent (Rosellon & Medalla, 2017). The industry sector averaged only 33 percent, to which manufacturing contributed the most value-added and growth, while agriculture averaged 12.3 percent (ibid). This structural composition is typical to economies attempting to catch up with industrialized countries. In catch-up economies, the agriculture sector remains substantial in terms of the labor force it employs and its value-added to GDP, but wages are low, production is inefficient and growth is stagnant 57. While growth is seen in the industrial-manufacturing sector, it is very gradual and thus, not enough to provide opportunities for mass employment. And, although the services sector is growing rapidly, its growth is attributed to sub-sectors that absorbs limited employment e.g. low-tech content and low-growth paths.

The Philippines’ favorable GDP growth over the period has been riding the back of two advances, both of which are mitigated. The first is consumption spending which has comprised around 70 percent of GDP growth, rather than direct investments in production58 ; and the second is unprecedented Overseas Filipino Workers (OFW) remittances coupled with Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) industry revenues that remain largely un-invested in productive sectors59. The growth and strength of the services sector has been limited since it largely hires skilled workers (Aldaba 2013; Usui 2011).

Moreover, the Philippine economy literally stands on Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) which comprise 99.6 percent of formal businesses in the country (2012 National MSME Statistics as cited in ADPC & DTI, 2016). MSMEs also generate the most jobs among all enterprises in the country at almost 65 percent of the total, or 2,316,664 jobs (ibid). However, despite the strong policy support from the government since the 1990s, MSMEs’ contribution to value-added when compared with large enterprises is at a measly 35.7 percent as compared with 64.3 percent for the large companies.

In light of all the foregoing, it is the revival of the manufacturing sector that is seen as the turnkey for accelerating industrialization and generating jobs for most of the labor force including unskilled workers, and thus for inclusive growth (Rosellon & Medalla, 2017). Within this context, MSMEs would be facilitated to enhance their capacity for innovation and marketing, upgrade their technology and productivity, latch onto global value chains and production networks, and ultimately graduate to higher levels of business and value-added capabilities. Moreover, job-generating agriculture-based manufacturing industries, especially small-holder farmers’ and agriculture cooperatives would also be promoted by assisting them in product development, value-adding, and in integrating themselves into big enterprises for marketing and financing purposes. In addition, since the Philippines is naturally endowed with scenic natural landscapes packed in its 7,107 islands, and is recognized as one of the most diverse countries around the world, eco-tourism is considered to be a potential big source of employment and value-added.

The sustainability of the Philippines’ modest socio-economic gains, along with its future economic potential, are constantly threatened by the unique location and physical conditions of the archipelago that makes it highly vulnerable to natural hazards, the effects of which may be amplified by climate change. Even without climate change, the varied and mounting environmental problems facing the country—deforestation, degradation of coastal and marine resources, loss of biodiversity, soil erosion, urban congestion, deteriorating air and water quality, poor management of solid and liquid wastes, among others—exacerbate the country’s vulnerability weakening its capacity to handle natural calamities and man-made disasters. All these factors contribute to serious impacts on natural ecosystems with cascading impacts on food security, water security, livelihoods, human health, infrastructure, energy security and human settlements (ILO, 2014).

The country is a low-carbon-emitter, but is consistently ranked in the Top 10 in Long Term Climate Risk Index61 and is considered in extreme risk to natural disasters62 . Specifically, climate change is expected to impact three fourths of the country’s crop and livestock production due to drought extreme weather events and climate-induced rainfall variability (Cruz et al., 2017; NEDA, 2015). Water availability, stream flow and groundwater recharge are highly affected by changing rainfall patterns which has serious consequences for domestic, food and beverage, industrial, dam operation and hydro power generation (Cruz et al., 2017; Tolentino et al. 2016; Lasco, 2012; Miller, Alexander, & Jovanovic, 2009). In built up areas, high temperature, extreme rainfall and strong winds pose potential damages to infrastructures (USAID, 2017). All these will repeatedly interrupt economic development, and will hit two groups the hardest: MSMEs and poor workers.

Philippine MSMEs are resource-constrained, have weak adaptability and limited access to a broader set of coping strategies and are thus highly vulnerable (Ballesteros & Domingo, 2015). Disaster events affect all facets of businesses – capital, assets, supply chains, product market and labor. Meaning, disasters compromise business continuity and recovery; physical damages and disruptions in supply and labor can cause temporary business closure while structural repairs to buildings and recovery or replacement of damaged equipment needed to restore operations require large amount of resources (ADPC & DTI, 2016). Likewise, the poor is most likely going to be hit because of the effect of disasters on labor.

The challenge is two-fold: to pursue economic growth that is environmentally-sound and socially-just. Meaning, whatever pathway taken to economic development should be based on a new engine of growth and generator of decent jobs that can contribute significantly to poverty eradication and social inclusion. The world’s answer is a Just Transition to a Green Economy. Transitioning to a green economy hinge upon the continuing strive for more energy efficient production and consumption, the adoption of renewable energy systems, and the pursuit of low-carbon growth (ILO, 2015; ILO, 2017). Justly transitioning means this new paradigm of growth fueled by green and decent jobs is directly connected to the sustainability of livelihoods and societies and their natural resource base, and ultimately to improving the well-being of people and communities.

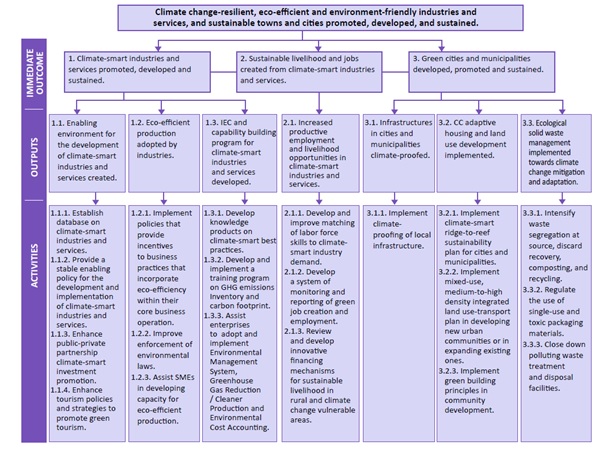

CSIS Theory of Change

CSIS Highlights

Governance Readiness to Adapt

During the reporting period, strategic frameworks, roadmaps, and plans which (i) enhance environmental performance of existing sectors/industries, (ii) enhance green sectors/industries, and (iii) mainstream and operationalize or pilot international just transition and green economy principles are enacted. These operationalize the policy direction on mainstreaming climate change and disaster risk reduction as these contribute to a just transition to an environmentally-sustainable or green economy as part of adaptive-mitigation. To support this, various government programs and services are thus implemented at the national, subnational, and sectoral levels. Stronger convergence among government agencies, policy coherence, and institutional capacity-building are also needed. This transition entails the creation of an institutional structure that covers (i) environment, (ii) labor, employment, and decent work, (iii) trade and industry, and (iv) cross-cutting concerns.

Enabling policy frameworks have already been placed to support coordination and cooperation among government agencies with mandates, responsibilities, authorities, and accountabilities (RAAs) over each cluster, towards this transition. Additionally, engagement of private and public stakeholders was ensured in the formulation and enactment of these policies. However, strengthened collaboration is yet to be seen as most of inter-agency engagements are observed to be limited to project-based or project-driven contexts. Although, this is expected as these partnerships are still in their early stages of institutional development.

Two tracks of capacity building interventions are implemented: (i) awareness-raising, technical facilitation, and hands-on mentoring, and (ii) vocational courses and trainings. The first track targeted public and private agencies crucial to the transition and aimed to build confidence and trust among these agencies in the formulation and execution of policies, thereby contributing to adaptation and adaptive-mitigation preparedness. As such, this track has been effective in terms of use of outputs, relevant in terms of stakeholder coverage, and logical and efficient in the timing and modes of delivery. The second track consisted of programs developed by the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA) to ensure that the demand for a skilled green workforce is met, which resulted in a big number of enrollees trained on green skills. However, if these actually meet demand, forecasts are yet to be seen as further information is required. A number of knowledge management initiatives to support green economy and green jobs promotion have also been established and implemented in several forms which contributed to adaptation and adaptive-mitigation preparedness. Information management systems to establish sector or industry state-of-the-art, establish a baseline and reference for future progress monitoring, and inform continuing policy-making and programming are developed to cover decent work, green jobs, and climate change information. Technical studies and seminal surveys to establish state-of-the-art baseline needs and demands are conducted covering green jobs, greening initiatives and disaster resilience assessments, small and medium enterprises, and greening potential and readiness of selected industries. Guidelines, manuals, protocols and tools to inform uptake of developed, tested and prioritized measures are formulated covering greening of business operations and value chains, and just transition. Orientation and awareness-raising informational materials are produced covering green practices for enterprises, national and local government units (LGUs), workplaces, and trade unions.

Adaptation Action Implementation

A number of measures to green the economy in terms of industries and services, and jobs have already been implemented way before the NCCAP which mostly are under the traditional sectors (e.g. natural resources management, energy efficiency, waste reduction). Further, other NCCAP themes also include greening measures such as (a) climate resilient agriculture and fisheries production, sustainable land management and sustainable agriculture and agroforestry; (b) sustainable natural resources management to address the anthropogenic pressures degrading forest, coastal, marine, watershed, river basin, riverine and other ecosystems within the reef to ridge spectrum, and ecosystems-based adaptation to deal with the climate-induced risks to these ecosystems; and (c) linked disaster risk reduction and management and climate change adaptation. However, whether the jobs created under these sectors are truly green is a question – on the one hand, these are considerably green given the nature of their activities, but from a Decent Work standpoint, it may not be the case given their working conditions. This is where the just transition is crucial as it paves the way for better working conditions and opportunities.

On the creation of green cities and municipalities, a number of measures are also implemented to pave the way for enhancing resiliency and transitioning to low carbon development. These are in the form of (i) piloting/ demonstration of green cities and municipalities, (ii) capacity building and (iii) policy development on mainstreaming climate change and environmental sustainability in land use plans, transport systems, buildings, and local industries. Overall, the just transition is evident at the subnational level, given the green initiatives and practices being implemented by LGUs and local industries. However, some aspects of greening cities and municipalities need to be strengthened, e.g. solid waste management, and public transport systems. Three types of privately-financed and public-funded financing schemes are made available for industries, enterprises, and LGUs: (i) support for green businesses and green production of goods and services, (ii) climate-proofing of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs), and (iii) risk financing mechanisms. What needs to be done is to ensure better access to these schemes by MSMEs through further capacity building, improved targeting, and analyses of barriers.

Mitigation Co-benefits

The sectors identified in the Philippines’ Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs), namely agriculture, energy, forestry, industry, transport, and waste are also the sectors targeted for greening by the Climate Smart Industries and Services (CSIS). Additionally, some mitigation options in these sectors are also identified as activities under CSIS (e.g., bus rapid transit systems, solid waste management, energy efficiency). Therefore, both the mitigation actions in the INDC and the activities and outcomes of CSIS are correlated and corollaries of each other.

Contributions to Enhancing Adaptive Capacity, Reducing Vulnerability and Sustained Development

Adaptation and adaptive-mitigation measures implemented in this period contribute to sustainable development outcomes in three key areas: (i) CSIS promoted, developed and sustained; (ii) sustainable livelihood and jobs created from CSIS, and (iii) green cities and municipalities developed, promoted and sustained. Under the first outcome, accomplishments of the country’s National Energy Efficiency and Conservation Program are noted as significant contributions, but needs further improvements in order to benefit from energy savings this program can generate. On the second outcome, given only but baseline data, it can be considered that the just transition into green and decent jobs is underway. A monitoring system for green jobs is thus needed to measure progress and inform decision-making. Finally, on the third outcome, the number of Seal of Good Housekeeping recipients provides good indication that the LGUs are underway towards the just transition. This indicator is used as a sound proxy since the Seal of Good Housekeeping is rendered to an LGU that passes three core assessment areas, one of which is Disaster Preparedness, and at least one from the essential assessment areas – Business-Friendliness and Competitiveness, Peace & Order or Environmental Management.

-

RESOURCES

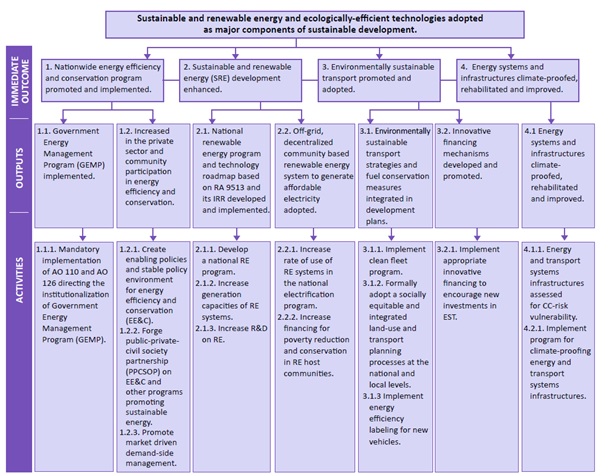

Sustainable Energy

SE Adaptation Context